|

|

BWV 524 Quodlibet (Fragment) “Was seind das vor grosse Schlösser”

By Thomas Braatz (December 2004) |

|

Contents |

|

Description

Provenance

History

Major Background Sources in Chronological Order

Translation

Detailed Commentary and Translation Problems with Possible Interpretations

Musical Elements

The Recording |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

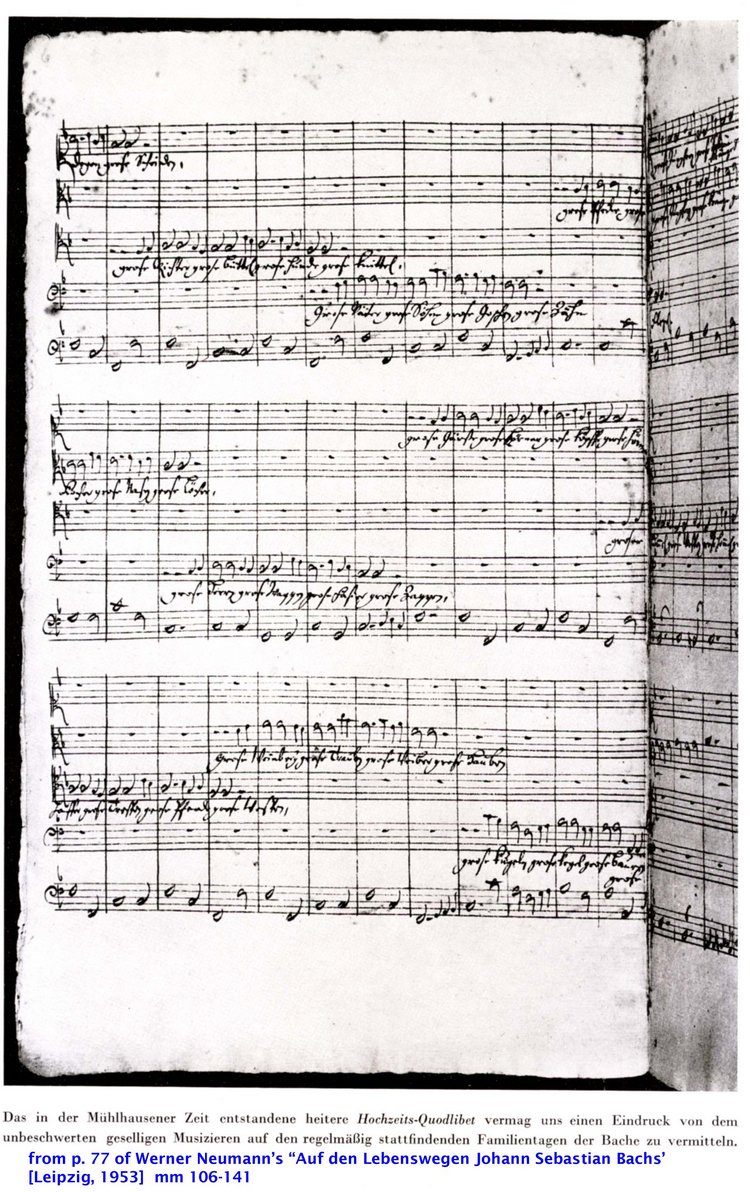

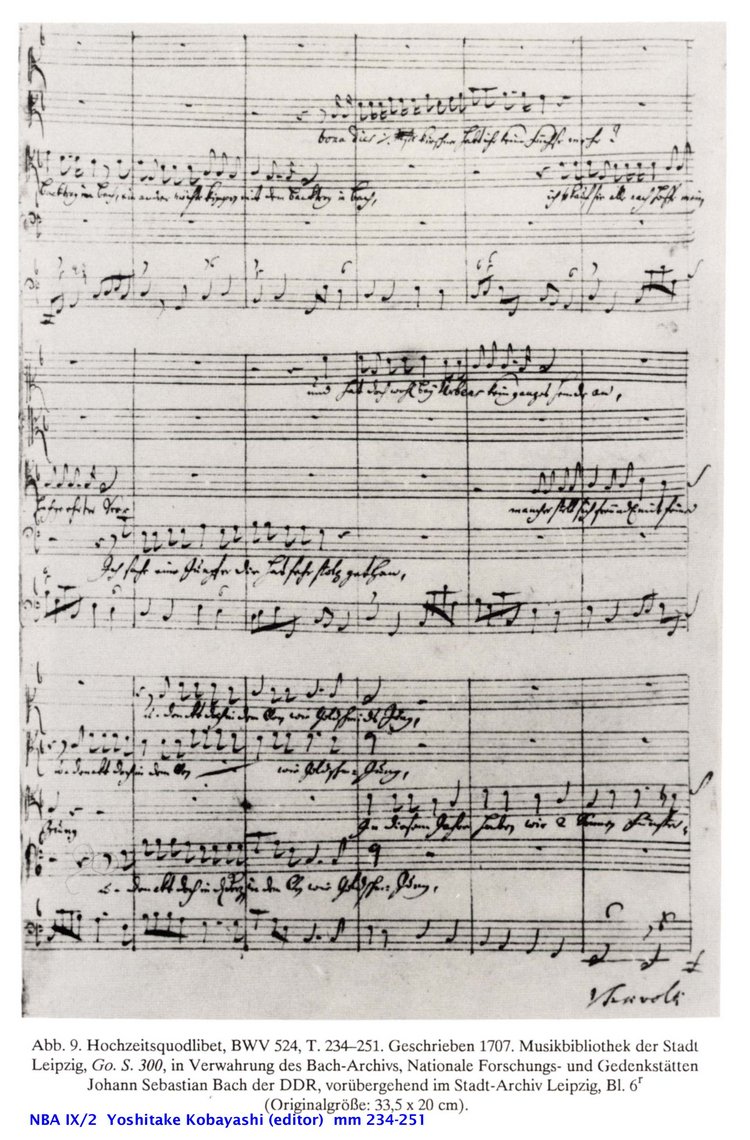

Description (from NBA KB I/41, pp. 50-55): |

|

The autograph manuscript can be described as follows:

1. There are three large sheets. Each sheet, when folded, yields 4 pages, hence there are 12 pages of handwritten music. The outer sheet containing at least 2 to 4 pages of music has been lost. It would probably have had an extra title page indicating the specific occasion and listing the voices and instruments for which it had been composed (possibly even a set of parts).

2. This is a clear copy which indicates that Bach copied it from another earlier draft.

3. Whether a set of parts ever existed is unclear. |

| |

|

Provenance: |

|

The existence of this autograph score (clear copy) fragment can be traced only back to 1932 where it was part of the collection of musical documents owned by an Eisenach bank official, Manfred Gorke. This collection (700 items) was purchased in toto by the City of Leipzig in 1935. It is conjectured that it might have belonged to Count Christoph Ernst Abraham Albrecht von Boineburg (1752-1840) who may have received it as a present from Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach with whom he was on friendly terms.

Text:

The author of the text is unknown, but it must have been written no later than 1708.

The text of this ‘Catalog-‘quodlibet contains, among other things, Latin quotations and makes use of the technique associated with the quodlibet of the catalog type.

A reference to two eclipses of the sun in one year has yielded the possibility that the year in question could only be 1705, 1706, or 1708 since 1707 had only partial eclipses in the region.

Some particularly troublesome words in the text are (measure numbers are given):

The full text is as follows:

15-20: “Ergo tanto instantius debemus fugere terrene, quanto velocius auffugiunt caduca et vana.” = “The faster earthly impressions pale due to their invalidity and futility/vanity, the more urgently we will need to flee from them.”

28: “Texel” = a Dutch, North-Sea Island situated just outside of the Zuidersee

31 ff.: “Mir plezt er meine Hosen” = He sews patches on my pants

42-43: “Probatum est” = as has been tried out/tested

69: “Salome” = possibly a reference to Maria Salome Wiegand, née Bach (born in 1677 in Eisenach, died in Erfurt in 1727,) who was Bach’s eldest sister.

79: “Gosche(n)” = South German/Austrian word for ‘mouth’ with numerous pejorative connotations.

90: “Orlochschiff” = a Dutch ‘man-of-war’ ship

131: “Trespen” = a weed growing under a grain crop

147: “Lacken” (“Lachen”) = puddle

157: “Leinwath” (“Leinwand”) = canvas

172 ff.: der sehr schlaue Cypripor” = a derivation of ‘Cypris’ an epithet for Aphrodite which has been incorrectly equated with Cupid; or more likely this is an allusion to an orthodox professor of theology, Ernst Salomon Cyprian (1673-1745.)

193 ff.: “Pantagruel” = an allusion to François Rabelais’ (1532-1552) novel “Gargantua and Pantagruel.”

195 ff. “trägt blaue Strümpfe an,” which in turn is derived from “Blaustrumpf” [‘blue-stocking’] = someone who has been revealed as a schemer, betrayer, show-off/big-mouth who appears as “der Schwarze” [‘the black one’ – ‘devil’] with a “Hinkefuß” [‘club foot.’]

210: “Koffent” [“Konventbier”] = a light, thin-bodied, watery beer

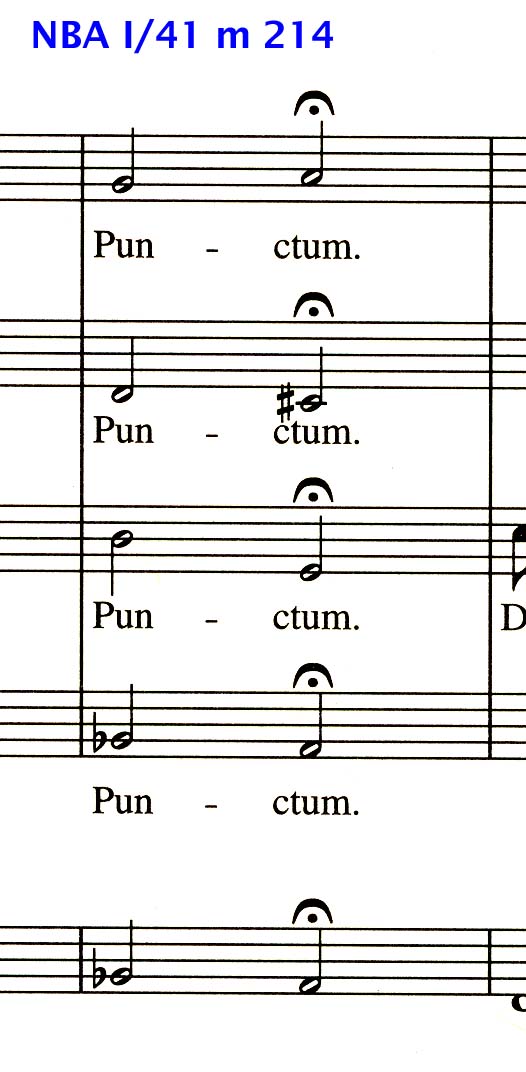

214: “Punctum” = ‘and that’s that,’ this is the end, stop it, no more talk

215-222: Dominus Johannes citatur ad Rectorem Magnificum hora pomeridiana second propter ancillam in corona aurea. = John is being asked to appear before the superintendent (or university president) at 2 o’clock this afternoon on account of the matter of the waitress at the Golden Crown Tavern.

247 ff.: “und denkt doch in dem Herzen wie Goldschmieds Jung” = ‘go, get lost;’ ‘you know what you can do,’ and various coarser variations of this

254: “Scheps” = a very heavy and fattening Beer from Breslau

261: “Brabant” = the central region of the low lands in Holland and the Belgium – it was still partially under control of the Spanish c. 1700.

262 ff.: “hat geboren eine alte Frau eine junge Sau” = ‘an old woman has born a young sow’ -- possibly a pun represented in music in m. 246 where the bass intentionally moves (musically in an improper manner) in octaves with the soprano.

Questions of authorship and date of composition:

Based upon the watermark and the analysis of the handwriting, the clean copy that Bach prepared must have been completed at the latest by July of 1708 (before he moved to Weimar.) The actual date of the original composition will have to remain open to speculation. It is also very difficult to decide to what extent Bach may have provided the text or even a part of it. There are no other compositions among his early works with which this can be stylistically compared. In any case, there are relatively few corrections of a minor nature; only in m. 270 did he switch the tenor and bass voices around.

A possible locale for performing this music would most likely be Erfurt, a university town, since there are numerous references (Latin quotes and terminology and direct references to students: “Studenten seind sehr fröhlich, wie ihr alle wißt” [“Students are very happy as you all know.”] Taking Forkel’s statement (from CPE Bach) about the annual Bach family get-togethers where quodlibets were improvised might also allow for consideration of Arnstadt or Eisenach as well.

A wedding is clearly the occasion for which this quodlibet was composed and performed, but it is not known which/whose wedding this might be. Possibly Bach prepared his clear copy as a presentation-gift to the wedding couple.

First Printing:

The first printed edition of this quodlibet was edited by Max Schneider in 1932 and appeared as part of the series “Veröffentlichungen der Neuen Bachgesellschaft” (Jg. XXXII, Heft 2) Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig.

The above information is primarily taken from the NBA KB I/41, pp. 50-55. |

| |

|

History |

|

The following information on the ‘quodlibet’ is taken in part from the articles on this subject as given in the Grove Music Online [Oxford University Press, 2004, acc. 12/2004] and written by Maria Rika Maniates (with Peter Branscombe and Richard Freedman) and from the article by Kurt Gudewill in the MGG [Bärenreiter-Verlag, 1986.]

Quodlibet [Latin: ‘what(ever) you please’]

The history of this term can be traced back to Wolfgang Schmeltzl’s “Guter seltzamer und künstreicher teutscher Gesang, sonderlich etliche künstliche Quodlibet,” Nürnberg, 1544 where ‘Quodlibet’ is used as an abbreviation of “Disputatio de quolibet” to designate a composition using several voices that imitated, in a way, a scholarly exercise in disputation that was eventually encountered as part of the oral exams at the university. Although the scholastic tradition can be traced back to the Sorbonne University in France at the beginning of the 14th century, the later German form of it bears little resemblance to the serious form that it had had originally in France. In Germany this tradition suffered great corruption at the end of the 14th and the beginning the 15th centuries as is apparent from the silly, humorous, nonsensical appendages that were added to the end of serious disputations so as to maintain the dwindling, diminishing interest on the part of the saudience. One German example illustrates the idea of humorous parody found in such a ‘Disputatio’: a silly list/catalog of items are loosely combined under a ridiculous theme, “the objects forgotten by women as they flee from a harem.” As one can imagine, this situation became worse with time until the authorities tried to put an end to this type of exercise [In 1558 at the University of Heidelberg, this type of verbal quodlibet-disputation was explicitly banned because ‘it was of little use’ and usually degenerated into a ‘lot of humor that was insulting, humiliating and degrading;’ in other words, the jokes had become too caustic for the authorities. Hans Sachs (1529) had experienced this verbal form of quodlibet and referred to it as a ‘ridiculous, silly list/catalog.’

The earliest musical form of the quodlibet in Germany can be traced back to at least 1480, the date of the Glogauer Liederbuch which has examples of a particular type explained below. The musical form of the quodlibet continued to exist in Germany after Schmeltzl’s first reference to it in 1544 [obviously Schmeltzl was not aware of the Glogauer Liederbuch.] S. Roth, in his dictionary from 1571 refers to the quodlibet as a ‘durcheinandermischmasch’ [‘a thoroughly jumbled hotchpotch’ ‘various items completely mixed up and presented at random.’] J. Fischart refers to the quodlibet frequently in his satires and in his book “Geschichtsklitterung” [1575] where he even draws some parallels between the ‘mock’ disputation tradition with its comical lists of non-related items and the musical form of the quodlibet which continued to be in favor in the local student taverns or privately where the authorities could not reach the performers.

A foreign influence upon the method and subject matter of German quodlibets seems to come from Rabelais’ ‘Pantagruel’ which is mentioned specifically in Bach’s quodlibet. The lists of dishes and songs contained in ‘Pantagruel’ were well known beyond the borders of France, and yet France developed a different type of ‘quodlibet’ which has much more to do with repartee and witty riddles than the mere catalog listings that were in vogue in Germany. The French Renaissance composers did explore the possibilities of setting to music short citations of songs when the poetic text made reference to them.

Paralleling the development of the musical quodlibet in Germany, other countries had or were also developing various forms of ‘quodlibets’ with some similarities, but with some major differences when compared to the German musical quodlibet. Here are some of these forms: ‘Messanza’ or ‘Misticanza’ or ‘Incatenatura’ in Italy, ‘Ensalada’ (Spain), ‘Fricassée’ (France) , ‘Medley’ (England.)

Street cries have been presented in quodlibet form in various countries (certainly Orlando Gibbons comes to mind here.) Other forms bear some resemblance to the quodlibet, but are nevertheless distinct from it: ‘potpourri,’ ‘rôtibouilli,’ ‘pasticcio,’ ‘salatade,’ ‘farrago,’ ‘collage,’

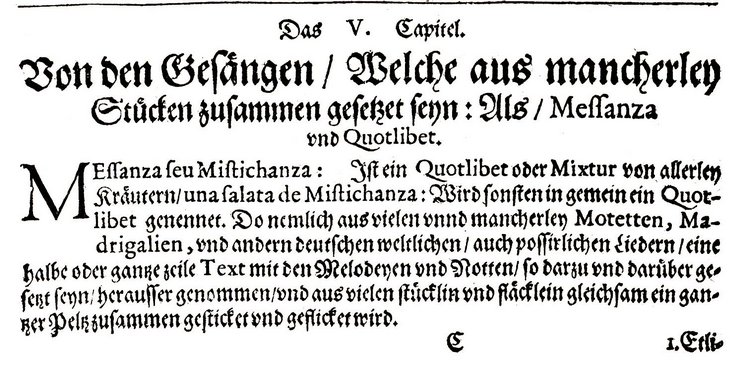

Michael Praetorius, in his ‘Syntagma musicum’ [Wolffenbüttel, 1619] Book 3, pp. 17-18, was the first to systematize and categorize the various types of ‘Quotlibet’ [sic]. Here is what he says:

Chapter V About the songs which are put together (composed) with various pieces coming from other sources: Known as ‘Messanza’ and ‘Quotlibet.’

‘Messanza or ‘Mistichanza’: This is a ‘Quotlibet’ or mixture made of all sorts of herbs ‘una salata de Mistichanza’: it is commonly known as ‘Quotlibet’ and called this because, specifically, it consists of either a half or whole line of text with its accompanying melody and notes placed above it extracted from many and various motets, madrigals, and other German secular songs that are comical in nature. These separate pieces/parts which are like patches are then sewed/patched together to make a complete fur coat from these patches.

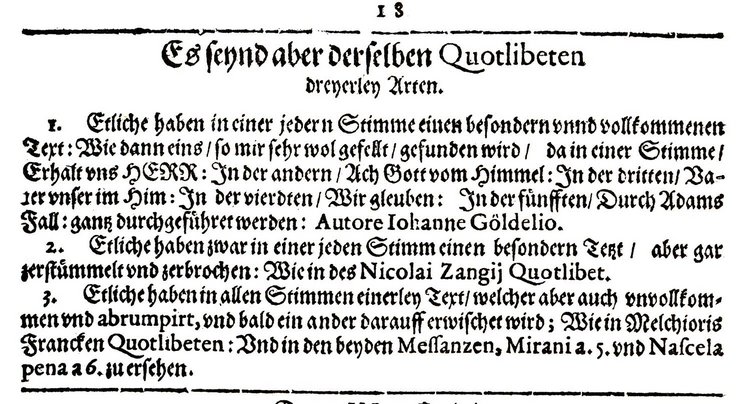

There are, however, three different types of ‘Quotlibets’

1. Some ‘quotlibets’ have in every voice a particular and complete text, as for instance in one ‘quotlibet’ which I found and like very much, where you will find in one voice the chorale “Erhalt uns Herr,” in another voice “Ach Gott vom Himmel,” in the 3rd voice “Vater Unser im Himmel,” in the 4th voice “Wir glauben,” and in the 5th voice “Durch Adams Fall.” All of these chorales are sung completely through from beginning to end. The composer is Johann Göldelio. [unable to locate information about this composer]

2. Some ‘quotlibets’ have, to be sure, a particular (different) text in each voice part, but they have been completely mutilated and broken apart into many pieces. An example of this can be found in Nicholaus Zangius’ ‘Quotlibet.’ [c.1570-c.1618]

3. Some ‘quotlibets’ have the same text in all voices, which, however, is incomplete and stops suddenly whereupon another different one is discovered in its place as is evident in Melchior Franck’s ‘Quotlibets’ and in both of his ‘Messanzen, Mirani’ a. 5 and ‘Nascela pena’ a. 6.

So, in essence, Praetorius says that a ‘quodlibet’ is a vocal composition with musical lines being constructed from:

1. Simultaneous (Polyphonic): the complete text/melody combinations for an entire verse of the chorale or song is sung by a single voice. The other voices do the same with different chorale melodies or secular songs that receive a similar treatment (various tunes or melodies are heard simultaneously)

2. Successive: (Polyphonic as well as Homophonic) the patchwork of quoted fragments (perhaps only incipits or certain memorable lines) can be found in each vocal part/line (non-simultaneously or successively as various texts/melodies may even jump about from voice to voice.)

3. Catalog/List (generally Homophonic): the same fragmentary texts may be shared by other voices simultaneously (block harmony or even unison) but they [the intentionally humorous texts] consist of sequential lists/catalogs that allude to strange or comical news items, to caricatures of known individuals, references to those singing or listening, etc.

In the MGG, Kurt Gudewill presents the types of ‘quodlibet’ in ascending difficulty from the most primitive to the more sophisticated types. He begins with the former:

1. The catalogue quodlibet

Its characteristics are a) a homophonic chordal style with voices generally singing the same text at the same time; b) there is a succession of various things or animals with various attributes.

Generally this type of quodlibet is not tied to inserting various, often unexpected quotations, but rather presents an extended list of items or situations that are very loosely linked if at all.

2. The same-text, ‘cento-’type quodlibet [‘Cento’ a literary composition formed by joining scraps from other authors – already known in antiquity.]

This type is somewhat more artistic and profound than the catalog type in that the melodic fragments from existing songs/chorales are imported and masterfully arrayed so as to form this patchwork which still depends primarily upon homophonic, chordal structures as the voices sing the same texts together sequentially.

3. The multiple-text, ‘cento-‘type quodlibet

This is a combination of the successive with the simultaneous principles which demands of the composer good knowledge of counterpoint. It gives the composer the opportunity to achieve witty and clever effects through surprising combinations.

4. The polyphonic quodlibet

This type of quodlibet requires the greatest artistry in that several songs/chorales are quoted simultaneously, each voice with a different one, and melded into a single composition.

Some possible subcategories that should be mentioned are:

1. The ‘tenor’ song quodlibet

This is combination of several song/chorale c. f. with freely moving counter voices with no c. f. Ludwig Senfl has some compositions of this type.

2. The ‘cantus firmus’ ‘cento’ quodlibet

This combines a top voice (descant) with the ‘superius’ part of Dunstable’s chanson “O rosa bella” with a tenor part consisting of a chain of song citations together wa contra tenor part that moves freely. This type of example found in the “Glogauer Liederbuch” [1480] is perhaps the earliest German

quodlibet. |

|

|

|

The ‘Spirit’ of the Quodlibet depends upon:

1.) the choice and application of elements primarily are derived musically from folksongs, very popular art songs, street songs [‘Gassenhauer’], street cries, fragments of liturgy cited as parody, solmizations, toasts for drinking, etc., while the textual elements can be based upon proverbs, quotations, onomatopoeia, puns, rules of grammar, spelling jokes, dialect variations, mixed languages, and Latin phrases, terms, and sentences.

2.) the quodlibet is very dependent upon the social environment in which it is sung, the occasion for which it was composed.

3.) the goal of the quodlibet was entertainment which involved as many people as possible. It was not simply a piece to be performed while all the rest of the audience listened.

4.) the quodlibet was sung at all levels of society, but primarily it was sung by pupils, students, young clerics, and musicians. From the content it is usually possible to tell which group would have sung it.

Praetorius’ example combining entire verses of disparate chorales being sung simultaneously can only be considered as having a distant relationship to the quodlibet.

What are the characteristics of BWV 524?

It depends fully upon the principle of sequence and enumeration using a homophonic, rarely contrapuntal style. Fragments of folksong melodies are occasionally quoted and only in a few instances do all the voices sing together. The text generally has end rhyme. |

| |

|

Major Background Sources in Chronological Order: |

|

Michael Praetorius, in his ‘Syntagma musicum’ [Wolffenbüttel, 1619] Book 3, pp. 17-18, was the first to systematize and categorize the various types of ‘Quotlibet’ [sic]. Here is what he says: |

|

|

|

|

|

[>>Chapter V About the songs which are put together (composed) with various pieces coming from other sources: Known as ‘Messanza’ and ‘Quotlibet.’

‘Messanza or ‘Mistichanza’: This is a ‘Quotlibet’ or mixture made of all sorts of herbs ‘una salata de Mistichanza’: it is commonly known as ‘Quotlibet’ and called this because, specifically, it consists of either a half or whole line of text with its accompanying melody and notes placed above it extracted from many and various motets, madrigals, and other German secular songs that are comical in nature. These separate pieces/parts which are like patches are then sewed/patched together to make a complete fur coat from these patches.

There are, however, three different types of ‘Quotlibets’

1. Some ‘quotlibets’ have in every voice a particular and complete text, as for instance in one ‘quotlibet’ which I found and like very much, where you will find in one voice the chorale “Erhalt uns Herr,” in another voice “Ach Gott vom Himmel,” in the 3rd voice “Vater Unser im Himmel,” in the 4th voice “Wir glauben,” and in the 5th voice “Durch Adams Fall.” All of these chorales are sung completely through from beginning to end. The composer is Johann Göldelio. [unable to locate information about this composer]

2. Some ‘quotlibets’ have, to be sure, a particular (different) text in each voice part, but they have been completely mutilated and broken apart into many pieces. An example of this can be found in Nicholaus Zangius’ ‘Quotlibet.’ [c.1570-c.1618]

3. Some ‘quotlibets’ have the same text in all voices, which, however, is incomplete and stops suddenly whereupon another different one is discovered in its place as is evident in Melchior Franck’s ‘Quotlibets’ and in both of his ‘Messanzen, Mirani’ a. 5 and ‘Nascela pena’ a. 6.<<]

[So, in essence, Praetorius says that a ‘quodlibet’ is a vocal composition with musical lines being constructed from:

1. Simultaneous (Polyphonic): the complete text/melody combinations for an entire verse of the chorale or song is sung by a single voice. The other voices do the same with different chorale melodies or secular songs that receive a similar treatment (various tunes or melodies are heard simultaneously)

2. Successive: (Polyphonic as well as Homophonic) the patchwork of quoted fragments (perhaps only incipits or certain memorable lines) can be found in each vocal part/line (non-simultaneously or successively as various texts/melodies may even jump about from voice to voice.)

3. Catalog/List (generally Homophonic): the same fragmentary texts may be shared by other voices simultaneously (block harmony or even unison) but they [the intentionally humorous texts] consist of sequential lists/catalogs that allude to strange or comical news items, to caricatures of known individuals, references to those singing or listening, etc.]

From Johann Gottfried Walther’s ‚Musicalisches Lexicon…’ [Leipzig, 1732]:

>>‘Quolibet’ (gall.) ‘Quodlibet,’ ein lateinisches aus 2 zusammen gesetztes Wort, nemlich ‘quod libet’ was einem beliebt; ist also eben das was ‚Mistichanza.’ Praetorius führet deren dreyerley Arten an, wenn er also schriebe. (1. Etliche ‚Quodlibeten’ haben in einer jeden Stimme einen besonderen und vollkommenen Text. (2. einige haben zwar in einer jeden Stimme einen besondern Text, aber gar zerstümmelt und zerbrochen. Und (3. etliche haben in allen Stimmen einerley Text, welcher aber auch unvollkommen und ‚abrumpir’t, und bald ein anderer darauf erwischet wird. s. dessen ‚Syntagma Tom. 3. p. 18. Weil auch, wenn sie aus weltlichen Texten bestehen, mehrentheils Schertz-Reden darinnen vorzukommen pflegen, als werden sie deswegen von einigen auch ‚Dicteria mordacia’ und ‚acuta’ auf Latein genennet. Hierbey verdienet das ‚Sentiment,’ so der ‚Auctor’ des ‚musicali’schen Trichters p. 85. von den ärgerlichen ‚Quodlibeten’ fället, gelesen zu werden.<<

[‚Quolibet’ (French) ‚Quodlibet’ is a Latin compound word made up out of two words: ‚quod libet’ which means ‚ ‘whatever pleases a person.’ It is the same as that which is understood as ‘Mistichanza’ {see below.} Praetorius lists three separate types which are 1.) some ‘Quodlibets’ have in every voice part a particular {specifically different from the other parts) text which is complete in itself; 2.) some have, to be sure, a different text in each voice part, but the text has been corrupted and broken up {sections of text left out or out of sequence;} and 3.) some have the same text in all voice parts, but this text is also incomplete, abruptly broken off, or abbreviated, whereupon another text from somewhere else is found following on the same vocal part. See Praetorius’s book “Syntagma’ book 3, p. 18. And also because these quodlibets, when the texts are secular, tend to include humorous/witty comments or statements in them, some people call them ‘Dicteria mordacia’ and ‘acuta’ in Latin. In this regard, it is worth reading what the author of the “Musical Funnel’ says on p. 85 when he speaks about the quodlibets that can annoy people. ]

>>‚Messanza’ (ital.) … oder ‚Mistichanza’ [ist] so viel, als ein ‚Quodlibet;’ wenn nemlich aus vielen Motetten und Madrigalien, weltlichen und possierlichen Liedern, eine halbe oder gantze Zeile Text, sammt den Melodien, herausgenommen, und aus solchen Fleckgen und Stückgen wiederum ein gantzes Lied gemacht wird. Kurtz: es ist ein aus allerhand Clausuln, auch unterschiedlichen Texten, die keinen Zusammenhang haben, bestehender Gesang.<<

[‚Messanza’ (Italian) … or ‚Mistichanza’ means about the same as the word ‚quodlibet’ as it refers to a composition which selects from many motets and madrigals, from songs of a secular and comical nature, a half or a whole lines of text together with their {associated} melodies, patches and pieces {bits} in order to create from these and entire song. In short, it is a song which consists of an array of clauses, but also of various texts which bear no relationship to each other.]

From Forkel's biographical accouon pp. 424-425 “The New Bach Reader” [Norton, 1998]:

>>…the first thing they did, when they were assembled, was to sing a chorale. From this pious commencement they proceeded to drolleries which often made a very great contrast with it. For now they sang popular songs, the contents of which were partly comic and partly naughty, all together and extempore, but in such a manner that the several parts thus extemporized made a kind of harmony together, the words, however, in every part being different. They called this kind of extemporary harmony a ‘Quodlibet,’ and not only laughted heartily at it themselves, but excited an equally hearty and irresistible laughter in everybody that heard them. Some persons are inclinded to consider these facetiae as the beginning of comic operettas in Germany; but such ‘quodlibets’ were usual in Germany at a much earlier period – I possess, myself, a printed collection of them which was published at Vienna in 1542.<<

Christoph Wolff from his liner notes to volume 2 of Koopman’s cantata series on Erato:

>>The Quodlibet BWV 524 survives only in fragmentary form: the first and last sides of Bach's autograph score, which was written in Mühlhausen no later than the middle of 1708 are no longer extant. The fragment begins with the final word of the missing opening section and ends with the words "Ei, was ist das vor eine schöne Fuge" — a reference to the preceding fugue. Without the beginning and ending of the piece, it is difficult to make any categorical statements about its overall four-part musical structure. The title, Quodlibet, is not original but relates to the mixture of texts of various provenance, which do not form a coherent whole and which alternate linguistically between German and Latin. The text -- the authorship of which is not known — teems with quotations, parodistic interpolations (the Latin passage "Dominus Johannes" is set psalmodically) and a plethora of coarse and concrete allusions (a battleship, two solar eclipses, India, Austria, Brabant and so on) whose individual meaning is often obscure, not least because the purpose of the work remains unclear. It may have been written for a wedding in academic circles and perhaps contains references to Bach's circle of family and friends.<<

From David Humphreys’ article in the “Oxford Composer Companions: J. S. Bach” Boyd, ed. [Oxford University Press, 1999]:

>>‘quodlibet.’ A composition based on a collage of pre-existing and usually familiar melodies. The earliest uses of the term in a musical sense date from the 16th century. There are two main types: the centonization quodlibet, in which fragments of the melodies are heard successively in the same voice, and the combinative quodlibet, in which two or more melodies are heard in combination in different voices. Quodlibet singing was especially popular in Germany, where it seems to have been associated with festive occasions such as Christmas and New Year, but equivalent forms also existed in Spain (the ensalada), France (the fricassee), and England (the medley).

Classic collections of quodlibets which could have been known to Bach include those by Wolfgang Schmeltzl (1544) and Melchior Franck (1622). A collection in a rather different style from near Bach's own time is the ‘Augsburger Tafelkonfekt’ (1733—46). Bach's interest in quodlibet singing is mentioned by J. N. Forkel (1802), who relates that improvised quodlibets consisting of a melange of `partly comic and partly improper' words were sung at the annual reunion of the Bach family in various towns in Thuringia.

Two compositions, one certainly and the other probably by Bach, are in quodlibet form. The Quodlibet (Variation 30) from the Goldberg Variations combines the bass line and harmonic matrix of the Aria on which the work is based with jumbled fragments of two tunes, which can be identified from a manuscript addition in a copy owned by Bach's pupil J. P. Kirnberger, as ‘Ich bin so lang nicht bei dir gewest’ and ‘Kraut and Rüben’ (the latter being a version of the traditional bergamasca dance tune). It has been suggested that the movement serves a symbolic function in relation to the set as a whole, representing the Saturnalia or New Year celebrations that mark the ending of the annual cycle.

The other, more problematical work in quodlibet form is the so-called ‘Hochzeitsquodlibet’ BWV 524. First published in 1931, soon after its discovery, it is in Bach's hand but, since the bifolium containing both the beginning and the end of the piece is missing, we cannot ignore the possibility that this is a copy made by Bach of a work by another composer. Scored for SATB with continuo, it sets a series of short texts, many of them comic verses. They contain references to places in the Arnstadt district and to a number of individuals, some of whose names correspond to those of members of the Bach family. Other texts are simply homely proverbs or bawdy jokes. The manuscript is written on the same paper type as the autograph of Cantata 71, composed for performance in Mühlhausen on 4 February 1708, and further evidence for a dating around the beginning of 1708 comes from one of the texts, which reads `In diesem Jahre haben wir zwei Sonnenfinsternisse' ('This year we have two solar eclipses'), referring to an astronomical phenomenon which was indeed visible over north Germany during that year.<<

From “Bach Handbuch” by Konrad Küster [Bärenreiter, 1999] pp. 529-530

[Translation from the German]

>>It is possible to penetrate even further into the realm of privately performed compositions [after the preceding section dealing with the Schemelli songs] with this piece written down by Bach at the latest by the middle of 1708. This composition (BWV 524) is so private that it is almost impossible to uncover concrete background evidence for it. This quodlibet fragment begins suddently with [the beginning section is missing] “Was seind das vor große Schlösser” and ends just as abruptly with a fugue on the words “…eine schöne Fuge!” after which a change in time signature to 3/2 makes clear that the ending of this piece is also missing. There can hardly be any doubt that most of the lines of text, which to the ear of an open-minded listener seem not to be in any kind of sensible, meaningful sequence, must have alluded to things or persons well-known to those singing and listening to the performance of this music. The only question that remains is whether Bach was the author of the text or the actual composer of the music. The ‘clear’ copy definitely in Bach’s handwriting does not speak against Bach’s authorship. In any case, this fragment was preserved in a non-customary manner when compared with the way most other works by Bach have been transmitted. It is very likely a presentation copy that would have been given to the married couple after its performance.

Bach’s composition is scored for 4 voices and continuo and reveals multifarious aspects of musical structure: solo voice presentations alternate with homophonic 4-pt. sections; there are frequent changes of time signatures and tempi; polyphonic treatments are kept simple and at a minimum (one exception is where Bach uses the chaconne form for the section “Große Hochzeit, große Freuden…”); and the recitative-like are interspersed among the other sections, but they bear little or no resemblance to the Italian-type recitative that Bach normally used in his cantatas. The latter feature is probably due to the fact the Bach is dealing with a caricature here. Stylistically this composition is so unique among Bach’s oeuvre that it becomes difficult to relate it to any other compositions by Bach.<< |

| |

|

Translation: |

|

What are those big castles swimming on the sea? and they’re looking bigger and bigger as they come closer? Friend or foe? Or how should I take this? But what do I see off in the distance? Tell me, who is riding into town? He’s carrying a big wheel on his back. This must be a sign that the executioner has died. He’s ridithat horse rather stupidly and he’s wearing a coat of mourning as well.

The faster earthly impressions pale due to their invalidity and futility/vanity, the more urgently we will need to flee from them.

Whoever wants to do some shipping in India will find that I have a lot of ships here. I am certainly not simply a shipping lout. {I do understand shipping quite well} I don’t need masts or sails, the way they do on the Texel, for a baking trough will do just as well {as a large ship} Take note, you gnarly individual you, what is the master tailor up to now?

He’s sewing patches on my pants, and repairing my clothes. If you need to use a baking trough as a row boat (or tub) oh, then you will arrive in a terrible state, because you will fall into the pond, the pond which is so cold and you will keep swimming in it, and continue swimming on in it, like a dried cod, this is a proven fact.

O you thoughts, why are you torturing my spirit so? Why do you want to waver when/since Hope is telling me to remain steadfast?

O, just look at the sour expression on Salome’s face That’s all because the groom is tickling her with the (pitch)fork. O, just look at how the house servants are eating up so much cheese and butter! If they were calves just like you, they would eat this fodder.

If you sit on a white horse with a spinning wheel almost all the country hicks would open wide their gaping mouth. If you sit on a large fox with a spinning wheel, people would practically die of laughter as they sobbed so much; If you sit on a large black horse with a spinning wheel, O, in this situation the mourning coat won’t even be suitable, fitting or proper attire. If you want to use the ‘Backtrog’ [baking trough/vat] as a boat instead of a man-of-war (destroyer), well, then you will soon be dipped/submerged/immersed into the water just the same way that the clumsy pike dive into the water.

A large wedding means great joy; large swords require large sheaths; great judges need to have strong bailiffs; large dogs require large sticks; tall fathers have tall sons, big mouths have big teeth; large arrows need large quivers; large noses have large nostrils; great noble gentlemen have large coats of arms; large barrels have large taps; large-sized barley consists of large kernels; big heads have big horns; large-sized oats means large weeds growing in the crop; large horses means the presence of large wasps; a large vineyard yields large grapes; large ponds mean large hoods; large metal balls are large bowling balls; farmers who farm/own a lot of land are lazy louts of the worst type; tall/large/big unmarried women require (extra-) large wreaths on their heads; large asses have large tails; a lot of loud laughter means being drenched to the skin from the tears created from laughing; large/tall women mean a lot of gossip; large handles/clappers/drumsticks are needed for large drums; large wasps mean the presence also of large bumblebees; a large canvas needs a large area for bleaching; and large baking vats/troughs require large ponds (to sink in.)

Oh, how I have been greatly deceived by that very clever Professor Cyprian!]

Dearest Ursula, light a candle for me so that I can see what I am doing! If you don’t want to light it for me, I’ll certainly find you in the dark. If you think a woman is bad, a baking trough is really much worse.

Pantagruel was a very funny man, and many a courtly servant is a devil in disguise; and if you scraped away the outer surface of a gold coin, there would be a lot of naked (penniless) people living in many a royal palace. If their ducats were of the same value as the large coins, then our neighbor’s wealth would be in the millions.

My back is still quite strong, I really can not complain about my situation.

You could probably carry, I would think, at least 20 sacks.

That must be a stupid ass who would rather drink thin beer than wine and sweat it out in a cold room and be sitting in a baking trough rather than in a ship.

Period. That’s final!

John is being asked to appear before the superintendent at 2 o’clock this afternoon on account of the matter of the waitress at the Golden Crown Tavern.

Students are generally very happy-go-lucky, as you all know, as long as they still have a ‘bloody’/red cent left in their wallet/purse.

If the gallows were a magnet and the tailor were made of iron, how many of them would make the trip to the gallows even today yet!

If I were the King of Portugal, why would I care about this? Let someone else sitting in the baking trough tip over into the brook.

Hello, hello, Mr. furrier, don’t you have any foxes any more? I am selling all of them at the court, highly honored Sir. I saw a young, unmarried woman who acted very proudly, but she did not even wear a full shirt down town!

Some people pretend to be very friendly with finely phrase words, and yet at the same time they think/feel in their hearts: “you know what you can do for all I care.”

This year we will have 2 eclipses of the sun, and in the Breslau Rathskeller they serve a very good heavy and fattening beer, and in my wallet/purse there is a cancer which is eating up all my money.

Listen, gentlemen, all of you, to the news of what has happened in Austria,

Listen, gentlemen, to all the things that have happened in the Brabant region,

That’s where an old woman gave birth to a young sow!

All of you are now cordially invited to eat some pot roast now!

Oh, what a nice fugue this is! |

| |

|

Detailed Commentary and Translation Problems with Possible Interpretations: |

|

C (Time signature)

(fragment)(SATB)…Steiß.

[rump/buttocks or ‘hind end’ of the body] This might have been an appropriately humorous word with which to end the first section of the quodlibet. As explained earlier, the “Glogauer Liederbuch” contains some of the earliest German examples of quodlibet. At the end of the song book is a section of purely instrumental pieces which were intended to follow the songs. Some of these are called “Schwanz” [tail] and relate to the Latin word ‘cauda’ which can mean, among other things, a musical ‘coda’ [‘musikalische Schlußerweiterung’ – a musical extension beyond the ending.] Some of these pieces are called ‘The Fox Tail,” “The Crane’s Tail,” “The Peacock’s Tail,” “The Rat’s Tail” “The Farmer’s Tail,” but then more ‘creative’ titles which no longer relate to ‘cauda’ = ‘coda’ are used later on: “The Cat’s Paw,” “The Ass’s Head,” and “The Crab’s Claw” [this piece with 3 voices can be played upside down – the crab goes backwards as well as forwards. Bach would certainly have enjoyed seeing and hearing this along with the quodlibets that are included in the vocal section! As explained earlier, “in Germany this [academic] tradition suffered great corruption at the end of the 14th and the beginning the 15th centuries as is apparent from the silly, humorous, nonsensical appendages that were added to the end of serious disputations so as to maintain the dwindling, diminishing interest on the part of the student audience.” The ‘fun’ really begins with the ‘caudae’ [the ridiculous appendages, the sole purpose of which was to be extremely entertaining.] This fragmented beginning of Bach’s quodlibet ending with ‘Steiß’ may have been the point where the quodlibet is set loose to pursue its primary goal of humorous entertainment.

Despite the hilarious non sequiturs that arise when patching together various verbal phrases as well as song fragments, many in rhymed couplets and representative of a crude meter and verse form called ‘doggerel,’ there seems to be a general theme that holds this thread together: the arrival of some of the wedding guests from afar with special emphasis upon travel by water. The hyperbole used to describe this transportation by water resorts to conjuring up images of the largest ships that anyone can imagine. They are as big as castles. Later on there is a reference to a Dutch man-of-war. The reality of the boat trip which may have brought the guests to their destination would point to a vessel of very modest means such as a barge or fishing boat. The frequent exclamations of “Backtrog, Backtrog” [a baking/dough vat/trough which would be a ridiculsmall boat indeed compared to the oversized warship that was as big as a palace/castle] reiterate the guest’s passage by boat, as humble as that might have been along with some harrowing experiences for those landlocked visitors who may have experienced this for the first time. The word ‘Backtrog’ [a baking trough for mixing the ingredients for making bread – these large troughs were made by carving out the trough form from a tree trunk and would easily be large enough for one or two people to sit in them and still (barely) remain afloat upon water] is quite possibly a deliberate pun made possible by the linguistic interchange between ‘ch’ and ‘ck’ which historically is still documented in family names like “Bachofen” [a baking oven, not an oven situated next to or over a brook.] Names like Johann Caspar Bachofen (1695-1755) and Johann Georg Heinrich Backofen (1768-1830) are found side by side in a musical dictionary. The entry for ‘backen’ [to bake] in the DWB clearly states that South German authors persisted in using ‘bachen’ for ‘backen’ well into the middle of the 19th century. If printed statements like ‘wir sind von einem teig gebachen’ [‘we have been baked from one (batch/type of) dough’] are documented, then it is even more likely that the spoken regional forms of German would also have used and understood this interchange between ‘backen’ [ to bake] = ‘ bachen’ [to bake.] Thus ‘Backtrog’ as used in Bach’s quodlibet could quite easily have been understood as ‘Bachtrog’ which would include the pun on the Bach family name. Possibly this could even be a reference to the fact that the ‘Bachtrog’ [the trough/vat in which the ‘Bach family dough’ = genetic material] represents the ‘baking trough/vat’ which could be used as a cradle for the babies emanating from the marriage being celebrated here. A ‘trog’ in German can be used for numerous things besides a vat in which the dough can be kneaded and allowed to rise before baking, but two indications for its use in a figurative sense are 1.) it is shaped like a small boat and hence can refer to a boat which does not sail very well [DWB documents this as well as the English use of ‘trough’ (which is basically the same stem word) as ‘a small primitive boat;’ 2.) it can refer to a ‘cradle’ as in the humorous definition: “Eine Wiege ist ein Trog zum Rütteln von Menschenkindern damit sie brav sind” [“A cradle is a trough used for shaking young children so that they will behave.”]

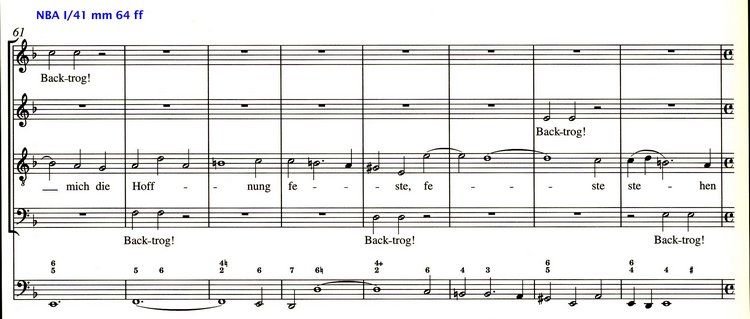

In the first 3/2 Adagio section, the tenor voice alone sings the text about being tortured by his wavering thoughts disturbing what would otherwise be a secure hope while the three voices not singing in this section interrupt these ‘thoughts’ by the tenor by interjecting the cry “Backtrog” at irregular intervals for a total of 11 times. Some possible interpretations of this might be:

1.) The guests who came to the wedding by boat were disheartened by the state of their vessel of conveyance. The cries of “Backtrog” only reminded them even more of the precarious state of their boat which resembled a baking trough/vat that was bringing some members of the Bach family [Bach = Back] to the wedding. The DWB substantiates the

2) The wedding couple, very intent upon maintaining their commitment based upon a firm hope, now begins to experience some doubts as the other members of the Bach family remind them of their duty to produce children to continue the family lineage. Now the cries of ‘Backtrog’ [= baking trough] are strong reminders by the other members of the wedding party for the couple not to forget to have more ‘Bach’ children. DWB equates the verbs: ‘bachen’ with. ‘backen’ both meaning ‘to bake’ but ‘bachen’ could also be construed to mean “to make Bachs” (to create more members of the Bach family.)

3) Another way to remind the wedding couple of their obligation to have more Bach children is to insistently reiterate the cry of “Backtrog” as a metaphorical picture of the cradle, perhaps even imitating the street cry of a vendor who has a “Backtrog” [= cradle] for sale which the wedding couple may soon need.

4) The DWB also instructs us that ‘Backtrog’ may figuratively represent a place to sleep: “ = eine gleich einem backtroge ausgehauene lagerstatt” [“a hollowed-out tree trunk which looks like a baking trough/vat.”] Thus the wedding guests might be distracting the wedded couple from its efforts at maintaining directed and steady thoughts and admonishing them to think of sleeping together very soon in a bed made for Bachs and for conceiving additional Bachs to add to the family line.

(S) Was seind das vor große Schlösser,

die dort schwimmen auf der See,…

(T)…und erscheinen immer größer,

weil sie näher kommen her?

[What are those big castles swimming on the sea?

and they’re looking bigger and bigger as they come closer?]

Obviously these two ‘statements’ do not normally belong together. The have been ‘patched’ this way for the humorous effect they elicit. The inanity of the statement: ‘Things are getting bigger as they come closer” will produce at least a chuckle among the listeners.

Now the attention is turned more directly towards discerning who is actually coming, this time on horseback. It is an unknown man in mourning who is carrying on his back a large wheel. It seems quite stupid for anyone to do this when a wagon would be so much better suited for this purpose. We are laughing at the obvious stupidity of someone who would persist in attempting to do this.

(B) Ist es Freund oder Feind,

(SATB)…oder wie ist es gemeint?

(S) Was muß ich von fern erblicken,

sagt wer reit' dort herein?

(T) Trägt ein großes Rad am Rücken,

der Henker muß gestorben sein!

(SA) Ei, wie reit' der Kerl so dumm,

(B)…hat einen Trauermantel um,

(SATB) hat einen Trauermantel um.

[Friend or foe? Or how should I take this (understand this)? But what do I see off in the distance? Tell me, who is riding into town? He’s carrying a big wheel on his back. This must be a sign that the executioner has died. He’s riding that horse rather stupidly and he’s wearing a coat of mourning as well.]

adagio (bc. has ‚’tardo’)

[slow with the bc being played hesitatingly, probably because of the hesitation on the part of the ‘pastor’ who is singing these words in a liturgical tone and trying to remember the Latin words or may have some trouble reading/singing them in a regular meter]

(T) Ergo tanto instantius debemus fugere terrena,

The ‘pastor’ sings: “It is necessary for us to flee from earthly impressions…”

(AT) quanto velocius aufugiunt caduca et vana.

“The faster they pale due to their invalidity and futility/vanity.”

Allegro

(S) Wer in Indien schiffen will,…

(A) …find' bei mir der Schiffe viel,…

(T)…ich bin eben kein Schiffersflegel,…

(B)…brauche weder Mast noch Segel,

(S)…wie man in dem Texel tut;…

(B)…denn ein Backtrog ist ebenso gut

(SATB) Notabene Knisterbart,

was macht der Meister Schneider?

(S) Mir plezt er meine Hosen,

(A) Mir flickt er meine Kleider,

(SATB) Mir flickt er meine Kleider.

(A) Braucht man den Backtrog vor den Kahn…

(T)…ei, so kommt man übel an,…

(S)…dann man plumpt man in den Teich, in den Teich so frisch

(AB)…und schwimmt darin, und schwimmt darin,

(ATB)…wie ein Stockfisch,

(SATB) und schwimmt darin, wie ein Stockfisch, probatum est.

[„Whoever wants to do some shipping in India {West Indies?}

…will find that I have a lot of ships here,…

…I am certainly not simply a shipping lout {I understand shipping quite well}

…I don’t need masts or sails,

…the way they do on the Texel (in the Netherlands;)

…for a baking trough will do just as well {as a large ship}

…Take note, you gnarly individual you,

What is the master tailor up to now [what’s he doing?]

He’s sewing patches on my pants,

And repairing my clothes

(altogether: “he’s repairing/mending my clothes.”

If you need to use a baking trough as a row boat (or tub)

…oh, then you will arrive in a terrible state,…

…because you will fall into the pond, the pond which is so fresh {cold}

…and you will keep swimming in it, and continue swimming on in it,

…like a dried cod, {stupidly like a dried cod in water}

This is a proven fact.

The line with ‘Backtrog’ and ‘Ka’ may be references to family names, “Bach” and “Kahn” of those present at the wedding while at the same time making the connection with the method of transportation that some of the guests may have had to use.]

adagio 3/2

(T) O ihr Gedanken, warum quälet ihr meinen Geist? –[(S) Backtrog!]

Warum wollet [(B) Backtrog!] ihr wanken, [(B) Backtrog!]

Warum wollet ihr wan---[(B) Backtrog! Backtrog!] [(A) Backtrog!] –ken,

da mich die Hoff—[(B) Backtrog!] --nung feste [(B) Backtrog!] ste—[(B) Backtrog] --hen heiß?

[O you thoughts, why are you torturing my spirit so? {11 interruptions with ‘Backtrog’ follow}

Why do you want to waver/vacillate,

Why do you want to waver when/since Hope is telling me to remain steadfast?]

C

(B) Ei, wie sieht die Salome so sauer um den Schnabel!

(SAT) Darum, weil der Pferdeknecht sie kitzelt mit der Gabel.

(S) Ei, wie frißt das Hausgesind so gar viel Käs und Butter!

(ATB) Wären sie Kälber gleich wie du, so fräßen sie das Futter.

(T) Wenn man mit dem Spinnrad sitzt auf einem großen Schimmel,

(SATB)…reißen ihre Goschen auf fast alle Bauerlümmel;

(SA) wenn man mit dem Spinnrad sitzt auf einem großen Fuchsen,

(SATB)…kriegen vor Gelächter die Leute fast den Schlucksen;

(SA) wenn man mit dem Spinnrad sitzt auf einem großen Rappen,…

(B)…ei, da will der Trauermantel

(T)…ei, da will der Trauermantel

(SATB)…gar nicht dazu klappen;

(SA) wenn man statt des Orlochschiffs den Backtrog will gebrauchen,

(T)…ach, da wird man alsobald in das Wasser tauchen,

(S) ach, da wird man alsobald, alsobald in das Wasser, in das Wasser, in das Wasser wie die Plumphecht tauchen,

(SATB) …wie die Plumphecht tauchen.

O, just look at the sour expression on Salome’s face (particularly the way she curls her nose = bird beak!)

That’s all because the groom is tickling her with the (pitch)fork.

O, just look at how the house servants are eating up (like animals) so much cheese and butter!

If they were calves just like you, they would eat this fodder.

If you sit at the spinning wheel the same way you sit on a white horse, or perhaps:

If you sit on a white horse with a spinning wheel

…almost all the country hicks (yokels) would open wide their gaping mouths {in astonishment}

If you sit at the spinning wheel as if upon a large fox, or perhaps:

If you sit on a large fox with a spinning wheel,

People would practically die of laughter as they sobbed so much;

If you sit at the spinning wheel as you would sit on a large black horse, or perhaps:

If you sit on a large black horse with a spinning wheel,…

…O, in this situation the mourning coat

…won’t even be suitable, fitting or proper attire.

If you want to use the ‘Backtrog’ [baking trough/vat] as a boat instead of a man-of-war (destroyer),

…well, then you will soon be dipped/submerged/immersed into the water just the same way that the clumsy pike dive into the water.

The reference to ‚Salome’ may well be directed at/connected with J. S. Bach’s sister ‘Salome’ {Marie Salome Bach {1677-1728} married Johann Andreas Wiegand on January 24, 1700, hence this quodlibet could not have been written/composed for their wedding as some commentators have incorrectly surmised.}

3/2

(S) Große Hochzeit, große Freuden, große Degen, große Scheiden;

(T) Große Richter, große Büttel, große Hunde, große Knittel;

(B) Große Väter, große Söhne, große Goschen, große Zähne;

(A) Große Pfeile, große Köcher, große Nasen, große Löcher;

(B) Große Herren, große Wappen, große Fässer, große Zappen;

(S) Große Gerste, große Körner, große Köpfe, große Hörner;

(T) Großer Hafer, große Trespen, große Pferde, große Wespen;

(A) Große Weinberg, große Trauben, große Weiher, große Hauben;

(B) Große Kugeln, große Kegel, große Bauren, große Flegel.

(SA) Große Jungfern, große Kränze, große Esel, große Schwänze.

(T) Große Lachen, groß Gepatsche, große Frauen, groß Geklatsche;

große Klöppel, große Trummel, große Wespen, große Hummel, große Wespen, große Hummel;

große Leinwand, große Bleiche, große Backtrög, große Teiche.

[A large wedding means great joy

large swords require large sheaths (sexual allusion)

great judges need to have strong bailiffs

large dogs require large sticks;

tall fathers have tall sons,

big mouths have big teeth,

large arrows need large quivers (another sexual allusion)

large noses have large nostrils (holes)

great noble gentlemen have large coats of arms,

large barrels have large taps (another sexual allusion)

large-sized barley consists of large kernels

big heads have big horns

large-sized oats means large weeds growing in the crop

large horses means the presence of large wasps

a large vineyard yields large grapes

large ponds mean large hoods (?)

large metal balls are large bowling balls

farmers who farm/own a lot of land are lazy louts of the worst type

large/big unmarried women require (extra-) large wreaths on their heads

large asses have large tails (another sexual allusion)

a lot of loud laughter means being drenched to the skin from the tears created from laughing

large/tall women mean a lot of gossip

large handles/clappers/drumsticks are needed for large drums

large wasps mean the presence also of large bumblebees

a large canvas needs a large area for bleaching (where the sunlight will bleach it)

and large baking vats/troughs require large ponds (to sink in.)]

This section is a parody of a certain succinct proverb style which can lead directly to a party game of generating similar ‘equations.’ It would be easy to imagine that each person in turn would have to come up with similar proverbs. The results frequently approach rather humorous platitudes.

This type of proverb was known in antiquity and can be found a many European languages. Here are some examples:

Gross Würde, gross Bürde. Lat.: Fasces, fasces.

Grosses Glück, grosse Knechtschaft. Lat.: Magna servitus est magna fortuna. (Seneca.)

Grosse Flüsse, grosse Fische, grosse Städte, grosse Diebe.

Port.: De grande rio, grande peixe.

Grosse Ehr, grosse Sorg. Dän.: Stor ære, stor bekymring/sorge.

Gross Gut, grosse Sorge. Dutch: Groot (veel) goed, groot (veel) zorg.

Gross Haus, gross Kreuz. It.: Gran casa, gran croce.

Grosse Herrschaft, grosse Sorge. Bohemian: Velike panování, velika starost.

Grosse Liebe, gross Leid (grosser Schmerz). French: De grand amour grand dueil et dolour.

Grosse Narren, grosse Schellen. Swedish: Stoor narr, stora biälror.

Grosse Schiffe, grosse Wasser. English:Great ships require deep waters.

Dutch: Groot schip, groot water. Italian: Gran nave vuol grand acqua.

Grosse Städte, grosse Sünden Swiss: Grossi Städt', grossi Sund.

I found about 75 German examples of this type of proverb pattern, but not a single one from the quodlibet appears in this list. It is quite apparent that all of the examples in the quodlibet were created ‘on the spur of the moment,’ possibly as the result of some family get-together prior to the wedding at which these sayings were recorded and given to the text author of BWV 524. There

Here is my list culled from a collections of German sayings/proverbs:

Grosses Amt, grosse Sorgen.

Gross Arsch, gross Bruo (Hosen).

Grosse Bücher - grosse Narren

Gross' Ehr', gross' Beschwer.

Grosse Ehr, grosse Sorg.

Gross Einkommen, gross Auskommen.

Grosse Fenster, grosse Scheiben

Grosses Feuer, grosser Rauch.

Grosse Flüsse, grosse Fische,

Grosse Städte, grosse Diebe.

Grosse Freud', grosses Leid.

Grosse Gefahr, grosser Gewinn

Gross Geld, gross Ehr'.

Gross Gewinn, gross Ausgaben.

Gross Glück, gross Sorge.

Gross Glück, gross Tück.

Gross Glück, grosse Gefahr

Grosses Glück, grosse Misgunst.

Grosses Glück, grosse Knechtschaft.

Gross Gnad, gross Ungnad.

Gross Gut, gross Gefahr.

Gross Gut, grosse Sorge.

Gross Haus, gross Kreuz.

Gross Haus, gross Unruh.

Gross Haus, gross Gast

Gross Herr, gross Recht;

Grosse Herren, gross Glück.

Grosse Herren, grosse Fehler.

Grosse Herren, grosse Gefahr

Grosse Herren, grosse Geschäfte.

Grosse Herren, grosse Sorge.

Grosse Herren, grosse Torheiten (Streiche).

Grosse Herren guter Tisch

Grosse Herren, grosse Sklaven

Grosse Herrschaft, grosse Sorge.

Grosser Hunger, grosses Ungemach.

Gross Horn, gross Thorn.

Grosse Keyserthum, grosse Reuberey.

Grosse Ke, grosse Schläge;

Grosse Schläge, grosse Beulen

Grosse Kinder, grosse Sorge;

Grosse Kirchen, grosse Kreuz.

Gross Kopf, gross Weh.

Grosse Künstler, grosse Lumpen.

Grosse Leute, grosse Tugend.

Grosse Leute, grosse Laster.

Grosse Liebe, gross Leid (grosser Schmerz).

Grosse Männer, grosse Fehler.

Grosse Meere, grosse Wellen.

Grosse Narren, grosse Schellen.

Grosse Nöten, grosse Hülfen.

Grosse Pracht, grosser Betrug.

Grosse Schiffe, grosse Wasser.

Grosser Schmuck, grosser Betrug.

Grosse Schuldner, grosse Duldner.

Grosse Seelen, grosse Taten;

Grosse Leiber, grosse Gräber.

Grosse Stadt, grosse Wüstenei.

Grosse Städte, grosse Sünden;

Grosse Sünden, grosse Strafen.

Grosse Stille, grosse Tiefe.

Grosse Sünder, grosse Büsser.

Grosse Sünder, grosse Heiligen.

Grosse Tugenden, grosse Fehler.

Gross Unglück, gross Glück.

Gross Wasser, grosse Fisch,.

Gross Wasser, grosse Fische;

Grosse Städter, grosse Sünder.

Grosse Wasser, grosse Kriege.

Gross Werk, grosse Gefahr.

Grosse Werke, grosser Lohn.

Grosse Winde, grosse Kriege.

Grosse Wohltat, grosser Undank.

Gross Würde, gross Bürde.

Grosse Zwecke, grosse Mittel.

(A) Ach, wie hat mich so betro---gen der sehr schlau---e, der sehr schlaue Cypripor!

[Oh, how I have been greatly deceived by that very clever Professor Cyprian!]

If this final statement before a tempo change reflects upon the long list of proverbs, it might then be possible that this professor made ample use of such proverbs in his lectures, but now with this new list which emulates the style of the proverb but turns these seemingly true statements upside down resulting in mere platitudes, the above line might reflect the humorous anguish of students who have come to rely upon such proverbs and the syntactical form in which they are couched.

C

(S) Urschel, brenne mir ein Licht an, daß ich dabei sehen kann!

(B) Willst du mir kein Licht anzünden, will ich dich wohl im Finstern finden.

(SA) Ist gleich schlimm das Frauenzimmer,

Ist doch der Backtrog, ist doch der Backtrog noch viel schlimmer;

(SATB) ist gleich schlimm das Frauenzimmer,

(B) ist doch der Backtrog noch viel schlimmer,

(A) ist doch der Backtrog noch viel schlimmer,

(S) ist doch der Backtrog noch viel schlimmer,

(T) ist doch der Backtrog noch viel schlimmer,

(SATB) ist doch der Backtrog noch viel schlimmer!

[Dearest Ursula, light a candle for me so that I can see what I am doing!

If you don’t want to light it for me, I’ll certainly find you in the dark.

If you think a woman is bad (crooked in shape), a ‘Backtrog’ [=baking trough where all the kneading of dough takes place, or if used as a bed, the ‘knutschen’ {kneading of human flesh – fondling, caressing to the point of love-bites}, or if used as a primitive boat it threatens to sink quickly when one or two individuals are in it] is really much worse (repeated numerous times.)

[‘Frauenzimmer’ can be a collective noun referring to the place in a building where most women primarily congregated (with men rarely admitted except for very short periods.) Sometimes the higher-ranking women had their own room for assembling while the women servants were situated in another room elsewhere. Beginning in the 17th century, there is evidence that ‘Frauenzimmer’ was also being applied both as a collective concept for women generally, but also to individual women. In the latter instance (in Bach’s time and well into the 19th century), referring to a woman as a ‘Frauenzimmer’ rarely, if ever, had a pejorative connotation as it does currently: ‘hussy.’]

(T) Pantagruel war ein sehr lustiger Mann,

und mancher Hofbedienter trägt blaue Strümpfe an.

(S) und streifte man denen Füchsen die Hautlein aus,

so gäb's viel nackigter Leute auf manchem Fürstenhaus.

(A) Wären denen Dukaten die großen Krätzen gleich,

so wäre unser Nachbar viel Millionen reich.

(B) Mein Rücken ist noch stark,

ich darf mich gar nicht klagen.

(AT) Du könntest, wie mich dünkt,

(SAT) du könntest, wie mich dünkt, wohl zwanzig Säcke tragen.

(B) Das muß ein dummer Esel sein,

der lieber Koffent säuft als Wein

und in der kalten Stube schwitzt

und statt des Schiffs im Backtrog sitzt!

(SATB) Punctum.

[Pantagruel was a very funny man,

and many a courtly servant wears blue stockings (is a devil in disguise)

and if you scraped away the outer surface of a gold coin

there would be a lot of naked (penniless) people living in many a royal palace.

If their ducats were of the same value as the large coins (mainly copper with surface gold removed)

Then our neighbor’s wealth would be in the millions.

My back is still quite strong

I really can not complain about my situation.

You could probably carry, I would think, at least 20 sacks.

That must be a stupid ass

Who would rather drink thin beer than wine

And sweat it out in a cold room

And be sitting in a ‘Backtrog’ [baking trough] rather than in a ship.

Period. That’s final!

(T) Dominus Johannes citatur ad Rectorem Magnificum hora pomeridiana secunda propter ancillam in corona aurea.

(A) Studenten seind sehr fröhlich. wie ihr alle wißt,

solang ein blutiger Heller im Beutel übrig ist.

(S) Wär der Galgen Magnet und der Schneider Eisen,

wie mancher würde noch heute an den Galgen reisen!

(T) Wär ich König in Portugal. was fragt ich darnach,

ein andrer möchte kippen mit dem Backtrog im Bach,

ein andrer möchte kippen mit dem Backtrog im Bach.

(A) Bona dies, bona dies, Meister Kürschner, habt ihr keine Füchse mehr?

(T) Ich verkauf sie alle nach Hofe, mein hochgeehrter Herr.

(B) Ich sahe eine Jungfer, die hat sehr stolz getan…

(S) …und hat doch wohl bei Urbens kein ganzes Hemde an!

(T) Mancher stellt sich freundlich mit feiner Zung…

(ABS) und denkt doch in dem Herzen wie Goldschmieds Jung.

(T) In diesem Jahre haben wir zwei Sonnenfinsternissen,…

(B)…und zu Breslau auf dem Keller schänkt man guten, schänkt man guten Scheps,…

(AT)…und in meinem Beutel regiert der fressende Krebs.

(SB) Hört ihr Herren allzugleich,

was da geschehen in Osterreich,

(AB) Hört ihr Herren allerhand,

was da geschehen in Brabant,

(SATB) Da hat geboren eine alte Frau

eine junge Sau!

(SA) Seid freundlich eingeladen zum Topfbraten!

(TB) Ei, was ist das vor eine schöne Fuge,

(SATB) …eine schöne Fuge!

3/2 Fragment lost

[John is being asked to appear before the superintendent (or university president) at 2 o’clock this afternoon on account of the matter of the waitress at the Golden Crown Tavern.

Students are generally very happy-go-lucky, as you all know,

As long as they still have a ‘bloody’/red cent left in their wallet/purse.

If the gallows were a magnet and the tailor were made of iron,

how many of them would make the trip to the gallows even today yet!

If I were the King of Portugal, why would I care about this

Let someone else sitting on the “Bachtrog” [baking trough] tip over into the brook. [Bach=brook]

Hello, hello, Mr. furrier, don’t you have any foxes any more?

I am selling all of them at the court, highly honored Sir.

I saw a young, unmarried woman who acted very proudly…

…but she did not even wear a full shirt (possibly only a camisole) at Urben’s place (possibly student slang Latin: ‘urba’: when in the city!)

Some people pretend to be very friendly with finely phrase words…

And yet at the same time they think/feel in their hearts the same way that the goldsmith’s boy does (“you know what you can do for all I care” “Go, get lost.”)

This year we will have 2 eclipses of the sun…

…and in Breslau Rathskeller they serve a very good heavy and fattening beer,…

…and in my wallet/purse there is a cancer which is eating up all my money.

Listen, gentlemen, all of you to the news of what has happened in Austria,

Listen, gentlemen, to all the things that have happened in the Brabant region (of Belgium and Holland),

That’s where an old woman gave birth to a young sow!

All of you are now cordially invited to eat some pot roast now!

Oh, what a nice fugue this is! |

| |

|

Musical Elements: |

|

From the standpoint of musicological scholarship, it seems relatively certain that BWV 524 is an autograph with the year of this ‘clean’ or ‘clear’ copy being rather firmly fixed. Since the original autograph score has not been found, there are still doubts expressed that the music is really Bach’s . Could he have simply copied a composition by another composer? In order to try to ‘prove,’ if this is possible, that this musical composition originated with Bach, it would be helpful to uncover/discover musical techniques that might be more characteristic of Bach’s music as we know it from other sources. The nature of this composition is rather unlike anything else that we have directly from Bach’s hand. Its intended audience is one limited to family members where two of them are being celebrated, not in church, but rather in a closed, private group of Bach-related families where greater freedom of expression would be allowed at such a celebration.

As indicated by the NBA KB, the author of the quodlibet text is unknown, but it seems quite likely that a number of individuals may have contributed certain lines or suggested them for inclusion. The long series of proverbs/sayings beginning with ‘Groß’ seem even to have originated as part of a group effort, possibly some type of game in the round where each subsequent individual, whose turn it becomes, must come up with a similar proverb and make it rhyme with a preceding one. The contributors were very creative and the results were worth conserving as a family memoir of the family gatherings preceding the actual marriage.

The line “What a nice fugue this is!” could easily have originated with Bach personally as he knew that other composers/musicians in the extended Bach family would immediately understand and appreciate the humor in his lackluster, rather primitively worked-out fugue that would provoke a great amount of laughter.

Some Specifics:

In mm 7 and 14, all the voices join in after the others have been singing mainly solos and duets. This is rather reminiscent of a technique that Bach continued to use in Leipzig with the opening mvt. of a chorale cantata where a short reiteration of the preceding exposition of a line of the chorale is added by the other 3 voices when the cantus firmus has finished singing. |

|

|

|

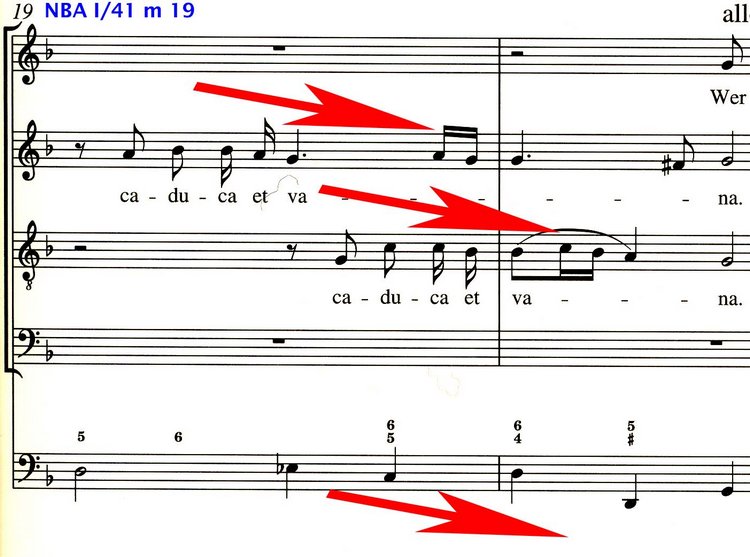

In mm 19-20 on the word ‘caduca’ [‘drooping/dropping down’] the musical lines express the same notion. |

|

|

|

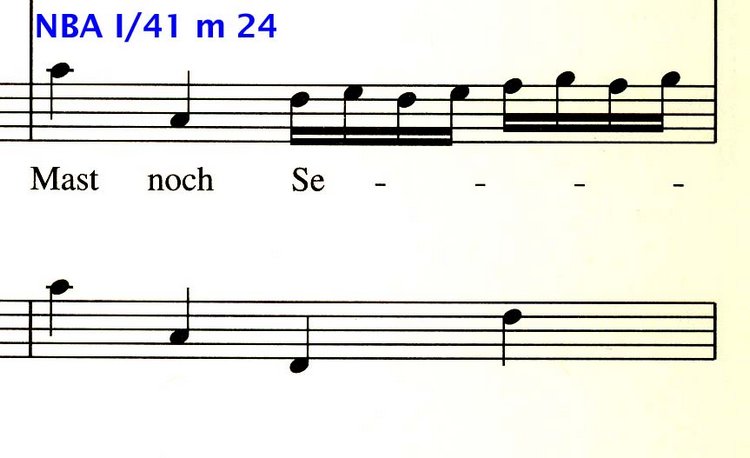

M 24 has the bass voice singing a special melisma on ‘Segel.’ What is interesting about this word painting which describes in music the sail being hoisted and fluttering in the breeze is that the entire statement is negated: the bass sings “I don’t need a mast nor do I need sails either.” This type of thing happens quite frequently in Bach’s sacred works when he uses word painting to illustrate the text. Bach will insist on describing in music the negative, that which does not exist or happen, just because a specific word allows for a musical illustration of its meaning. |

|

|

|

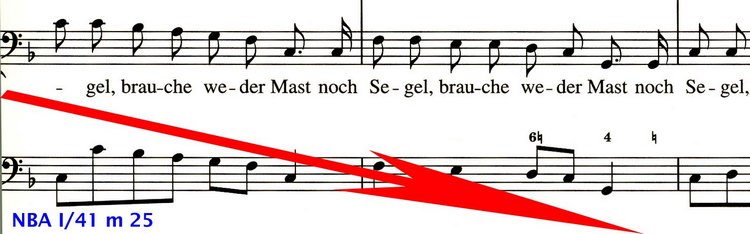

Bach illustrates in mm 25-26 musically what happens when one tries to remain afloat in a baking trough ‘without a mast or sails’: the bc descends 1 ½ octaves from a high C to a low G in just 2 measures. |

|

|

|

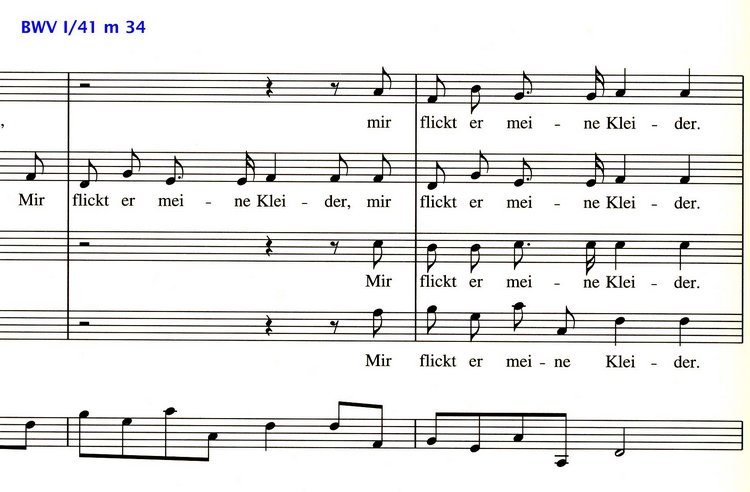

M 34 contains a mocking imitation by all the voices of what a single voice part has sung: “He’s patching my clothes.” This would very likely be sung in a mocking tone. |

|

|

|

In mm 37-38 “dann man plumpt in den Teich” [“then you will fall into the pond”], Bach has the melody line generally ‘fall down’ with intervals that leap downwards or descend scalewise. |

|

|

|

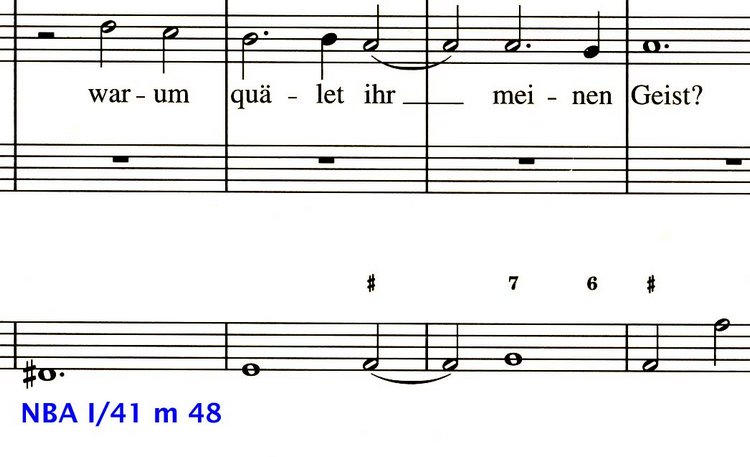

The next adagio section (3/2) mm. 45-69 contains numerous examples of musical illustration: mm 48-49 contain an example of hemiola just at the point when the text states “why are you torturing my spirit?” with the added complication of stretching out the normal beat to encompass two measures instead of one. |

|

|

|

On the word ‘wanken’ [‘to vacillate/waver’] the tenor has to sing jumping intervals (mm 53-54) or an extended melisma (mm 57-59.) |

|

|

|

“feste stehen” [‘to stand firmly’] mm 65-67 is illustrated by means of long, held notes which stand rather immovable on just a few notes that barely move from their established position.

During this 3/2 (adagio) section in which the tenor is trying to maintain steady thoughts by holding onto the long notes (the image of someone still paddling in an improvised boat which was originally a baking trough is still foremost in the minds of the performers and listeners), the bc makes a slow, sinking descent from a high Bb (m 51) to a low D in mm 64 & 68. This inevitable sinking takes place despite the cries of “Bachtrog” [baking trough] which are like warnings reminding the sinking ‘sailor’ that the baking trough was never meant to be used as a viable means of transportation. In essence, the others might by crying ‘baking trough’ to point out the reason for this slow sinking that is taking place. |

|

|

|

The next section marked ‘C’ (mm 69-102) consists of a game where a single singer begins a statement which is then completed humorously by the other singers with song fragments or invented texts that have to rhyme with the ending of the preceding statement. This produces combinations of non-sequiturs which nevertheless might have random textual connections beyond simply the end rhyme.

At m 92, when the repetitive game seems to be nearing an end, the theme of sinking in water is visited once again: the tenor, singing the words “…ach, da wird man alsobald in das Wasser tauchen” [“oh, soon I’ll sink into the water”], moves gradually downwards over a span of more than one octave. The bc accompanies this same movement along with the tenor, but when the soprano sings the same words (mm 96-101), the bc gradually drops over 2 octaves in just 4 measures. |

|

|

|

The 3/2 section from mm103-180 begins somewhat like a chaconne that is repeated at least 7 times, but other patterns are also used throughout this section. |

|

|

|

This is also in the form of a round game beginning with one singer/player and continuing around an imaginary circle. While the preceding section mm 69-102 consisted of a single voice followed by the remaining three or four as an answer, this time, with the exception of one short duet (SA), a single voice is answered by another single voice. This time, no attempt is made to rhyme with the final words of the preceding singer, but rather the end rhyme must be provided by the same singer in the form of a couplet which also demands another feature: a strict pattern established by insisting that each segment begin with the adjective ‘groß’ [‘big/large.’]

Beginning with mm 161-180, a subsection provides a reflection upon how all the singers (here possibly representing students) have been deceived by a theology professor who may have insisted upon the value derived from reciting moralistic proverbs similar to the ones which were invented here for this quodlibet.

The final section (in a C time signature) of this fragment (a missing 3/2 section follows it) begins with m 181 where a soprano (female) demands that another female, Ursula, should light a candle so that she can see what she is doing. The humor here is that the response to this request is given by the deepest male voice, the bass, who sings “if you’re not going to light a candle, I’ll find you in the dark anyhow.”

The two long chords at m 214 on the word “Punctum” after all the pitter-patter text of the preceding measures come as a welcome relief and express musically the emphatic need for a close here. |

|

|

|

MM 215-222 are similar to mm 15-20 in that both are sung by a tenor (in the latter instance partially together with the alto) in a quasi-liturgical tone that is unctuous but hesitating at the same time.

From mm 249-252, Bach has the bc descend stepwise down the scale for almost 1 ½ octaves, perhaps underlining the matter-of-factualness of the news item sung by the town crier. |

|

|

|

The word painting Bach employs to describe the swinging and rather empty money pouch involves melismatic 16th-note phrases in mm 255-256. |

|

|

|

Further news items about Austria and the Brabant region in mm 257-261 receives a similar, monotonous treatment as in mm 249-252, this time with the exact repetition of a bc pattern.

The pseudo-fintroduced at 265 barely manages to introduce the fugal subject properly with it counter subject in the soprano and alto voices (it is an invitation for all present to enjoy the pot roast which is now ready to eat. The tenor voice, in eager anticipation of the meal does not even state the fugal subject but rather joins with the bass to quickly announce the premature conclusion of the fugue (which might otherwise take too long and be too serious for this occasion) with “Ei, was ist das vor eine schöne Fuge!” [“Oh, what a beautiful fugue this is!”]

The final section of the quodlibet is missing. |

| |

|

The Recording: |

|

The recording of this work which I listened to was recorded as vol 2 of Koopman’s Complete Cantatas Series on Erato. It uses the same soloists featured in the other works contained in this volume. Of these singers, there are two who are far below average in their singing abilities and the beauty of their voices while Prégardien (tenor) and Mertens (bass) are far above average. Since this atypical work by Bach may call for a different treatment devoid of the usual seriousness necessary for a Bach sacred cantata, it is to be expected that some unusual effects in interpretation might be in order, but I find that when poorly controlled voices in the serious recitatives and arias are allowed to indulge in even greater than usual interpretative freedom in interpreting the humor of this quodlibet, the results of such singing are, for the most part, disastrous. |

| |

|

Written by Thomas Braatz (December 29, 2004) |

|

Quodlibet BWV 524 : Recordings | General Discussions

Article: BWV 524 Quodlibet (Fragment) “Was seind das vor grosse Schlösser" [by Thomas Braatz]

|

|

|